Thursday, February 02, 2006

Simultaneous Advantage

Introduction

Tactical Terminology

Since reading The Mammoth Book of Chess I have been using Burgess' tactical terminology in puzzling through difficult chess positions. This helps when I cannot understand an answer to a tactics problems, or when get stumped reading annotations comprised of variations with no supporting text. I hope that explaining these to myself "verbally" I will grasp the idea better.

Along the way, I have become somewhat non-standard in my tactical language. Naming tactics differently and seeing multiple tactics where others don't are my two biggest deviations from the norm. I have investigated both of these issues deeper, and this has led me to developing a new system for describing tactics.

Part I

Which Tactic is This?

White to Move

Tasc Chess Tutor, Step 2 Exercise 5b, #9

Answer: Bxf7+

What you call the Bxf7+ sacrifice depends on how you were taught. I seems ambiguous that might be called one or more of the following:

- Decoy

- Chasing

- Overworked defender

- Overloaded defender

- Deflection/Distraction

The most common response is that this is a decoy. This is like saying, "Moving the Black King to capture the Bishop is fatal for Black's Queen." I view this as a deflection, which is like saying, "The Black King's most important duty is to defend the Queen, and yet he moves away.". If the Black King was a Queen, it would look more like an overworked piece. I could see how someone could view these as chasing or overloading.

Aspects of Multiple Tactics

Another ambiguous area of is multiple tactics. I see this everywhere, or perhaps more accurately aspects of multiple tactics, although it's rarely described that way. Take this obvious checkmate in two for example:

White to Move

Rxh3+ gxh3 Rh3#

Four aspects seem to stand out in this position:

- Rxh3+ gets the g3 Rook out of the way of the d3 Rook, getting White ready for the final checkmate move

- Rxh3+ sacrifices a Rook for a pawn, a pawn that block's part of the h-file

- gxh3 draws a defender away from protecting the h3 square

- gxh3 turns a defender into a target on the h3 square

What do you call this kind of sacrifice for checkmate? Putting that question aside, is this multiple tactics? There is no hard and fast rule on what qualifies as multiple tactics, and few would give it that label. I personally like calling this outnumbering. Still, using a more common name for the initial Rook sacrifice leaves out those four aspects.

Part II

Simultaneous Advantage

Because of the two above ambiguities, I was at an impasse. My tactical descriptions were going to differ from the norm, and labeling many moves as multiple tactics would make things worse. As well, using other umbrella terms wasn't a satisfying solution, and that approach seemed too broad. I needed something else.

I focused on breaking things down further. I originally set out to categorize everything I knew about tactics: material gain, tempo related tactics like zugzwang and zwischenzug, forced mates, etc.. Just talking about forced moves brought up essentially forced moves, and so on. Unfortunately this list was too vast.

I finally focused exclusively on forced checkmates that start with a sacrifice. I set out to make an unambiguous vocabulary that was capable of tracking all of the tactical aspects in these positions.

I ended up with a simple 2x2 grid and viola all the parts began fitting together. I started with this:

Simultaneous Advantage When Sacrificing for Checkmate

move | away from a square | onto a square |

attacking piece | advantage(s) | advantage(s) |

defending piece | advantage(s) | advantage(s) |

This grid combines the attacker's plusses and the defender's minusses. An advantage is anything in the position that changes beneficially for the attacking side:

- the attacker's liability becomes a neutrality

- the attacker's liability becomes an asset

- the attacker's neutrality becomes an asset

- the defender's asset becomes a neutrality

- the defender's asset becomes a liability

- the defender's neutrality becomes a liability

The grid pinpoints the exact moment that an advantage is obtained. Each box has zero to many advantages written in it.

Here is my current draft of the advantages list and three detailed examples using it:

move away from a square onto a square attacking resulting checkmate threat resulting checkmate threat defending resulting checkmate threat resulting checkmate threat

piece

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

piece

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

piece

absolute pin

more vulnerable square

the King's flight squares

the King's flight squares

Notes:

It is assumed that the best offense and defense is used.

"Discovering" means a blocking (or masking) piece is moved, increasing the influence and mobility of one or more long-range attacking pieces. When this action occurs, one or more advantages are ascribed to it. "Discovering" is being used broadly here, as it includes situations where two long range pieces that form a battery move away from one another and where a Rook or Queen is behind a pawn that advances forward.

"Moving into an absolute pin" inherently implies that the piece has also moved into a capture that gives check, and this is treated differently from "moving into capture". Having both of those in a box means that in addition to the pinning threat, one or more other pieces are threatening to capture.

"Outnumbering" is similar to winning material by outnumbering an opponent's piece with more attackers than defenders. Here it means an attack on a square, so capturing is not required. The idea is that with more attackers than defenders trained on that square, an attack or interfering block from that square will succeed. This happen at any point, on either the attacker's move or the defender's move. If outnumbering happens on the defender's side, it might be thought of as overloading.

"Preventing counterattack" could be broken down further: preventing checkmate, check, perpetual check, perpetual chase, threats to capture pieces necessary for the final checkmate position, and threats to block pieces necessary for the final checkmate position. That list also applies to "withdrawing counterattack" advantage, which additionally includes unpinning one of the attacker's pieces, meaning both relative and absolute pins.

In "threatening check", the term "check" means threatening the defender's King with check or checkmate. When it occurs, further calculation is required to determine if it truly is a checkmate threat.

-=-=-=-=-

White to Move

Rxh3+ gxh3 Rh3#

Initial Advantages:

- Outnumbering to attack on h3

- Black King is on a vulnerable square for checkmate

- Black King only has the h7 flight square

- White threatens check on d8 and h3

move | away from a square | onto a square |

White: Rxh3+ |

|

|

Black: gxh3 |

|

resulting checkmate threat: Rxh3# |

White: Rxh3+ |

# |

-=-=-=-=-

White to Move

Bxg7+ Qxg7 Rh6#

Initial Advantages:

- Black King is on a vulnerable square for checkmate

- Black King has no flight squares

- White threatens check with Bxg7+ and Nf7+

move | away from a square | onto a square |

White: Bxg7+ |

|

|

Black: Qxg7 |

resulting checkmate threat: Rh6# |

|

White: Rh6# | # |

-=-=-=-=-

White to Move

Rxc6 Rxc6 b5/Rxc6 Bxa4 Qxa4

Initial Advantages:

- Black King is on a vulnerable square for checkmate

- Black King has no flight squares

- White threatens to capture on c6, d1, and e2

- White threatens check with b5

move | away from a square | onto a square |

White: Rxc6 |

resulting checkmate threat: b5# | |

Black: Rxc6 ------ Bxa4 |

|

resulting checkmate threat: Qxa4# |

White:

------ Qxa4# |

| #

# |

-=-=-=-=-

I find it striking that the first example has something in each of the first four boxes, something that it shares with the second example. Also striking is how few advantages were in boxes the third example, ...Rxc6 variation; most of the required advantages for checkmate were there to begin with, so this makes sense.

Part III

Common Knowledge

A well-disciplined player will typically do several things each turn:

- Determine if he can checkmate is opponent

- Determine if he must stop a checkmate threat

- Play for advantages appropriate to the position and stage of the game

In checkmate situations material superiority is meaningless, and as such it really isn't discussed in depth in chess books. Nonetheless, I think it deserves consideration. It seems that (at least) two modes of thinking are employed each turn, which I will call "checkmate thinking" and "non-checkmate thinking". These modes are very different, and confusion usually spells disaster. Not using checkmate thinking when it's an important part the position leads to mistakes: miscalculating checkmate threats because it looks like it loses material, ignoring checkmate threats for one side, etc.

Material

Material advantage is the biggest winning factor in non-checkmate thinking because it often leads to a win. The relative values of each piece is well known in its most simplistic form:

Material Values

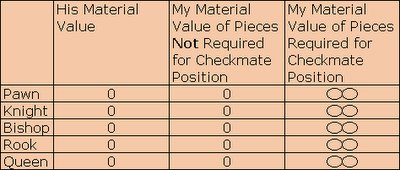

I think the other mode of thinking deserves its own table:

It's almost simpler to consider checkmate-thinking values, as it's a specific all-or-nothing ordeal (the "8" symbol on it's side means infinity). Having some material be worth 0 implies alot of things. Gain and loss have no meaning, and there is no way to sacrifice material per se, leaving only participants in the final checkmate position as having value.

Rewording

I started this investigation out mapping out all the different possible sacrifices for checkmate. I thought I was getting to the conclusion that all of these appear to be sacrifices for position, a well known idea.

Based on material devaluation in checkmates, I thought of changing the conclusion and call them exchanges for position. This would make the overall idea akin to even trades in non-checkmate situations, so giving up a full Queen potentially could be considered equal to getting a Queen for a pawn.

Next I thought, "What if the attacker doesn't sacrifice to start with, or maybe simply never sacrifices to achieve checkmate?" The grid still worked. Perhaps these all were forced checkmates.

Finally, allowing for the possibility that the defense could make an unforced blunder, it seems like these are simply checkmates. So here is the same grid, different title, now without the requirement to sacrifice or trade material:

move away from a square onto a square attacking resulting checkmate threat resulting checkmate threat defending resulting checkmate threat resulting checkmate threat

piece

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

piece

King's flight squares

King's flight squares

piece

absolute pin

more vulnerable square

the King's flight squares

the King's flight squares

The name "Theory of Simultaneous Advantage" came out of the realization that the most difficult tactical moves frequently involve multiple things happening on just one move. It is still under development, and it currently appears to be more like a vocabulary system than a theory. One thing that I am stating that does appear to constitute a theory is this:

The only way to achieve checkmate is through Simultaneous Advantage

In terms of the opening, the most instructive games are filled with moves that fit right into this kind of theory. Just think about the typical annotated game after 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 . Authors rave about White's castling preparation while threatening to inflict doubled pawns upon Black and hang the e5 pawn. This has been exhaustively studied, and it turns out that the 5. Nxe5 threat can be dealt with. Usually the prospect of handing Black a two Bishop advantage usually makes White choose not to capture on c6 on the next turn. Viewing the position in an immediate sense, the two Bishop advantage wouldn't immediately become a meaningful plus in the postion for Black if White trades his Bishop for the c6 Knight, so I can see it argued that White has achieved at least two if not three simultaneous advantages on move 3.

Normal Checkmates in the Theory of Simultaneous Advantage

To achieve checkmate the advantages all of these advantages must be accrued by the mating side before the last move:

The mating side has

1. the move

2. mobility to move the mating piece to the the mating square or, in the case of a discovered mate, has the mating piece on the mating square and has mobility to move masking piece off the mating line (i.e. it's not trapped)

3. a way out of check if he is in check. This move will deliver a discovered mate by having the mating side's King either capture the checking piece or move safely away leaving the defending side's checking piece, leaving that piece unable to stop the checkmate because of an absolute pin. This is here for completeness, as the situation is extremely unlikely to occur naturally:

White to move, and Black cannot interpose his pinned Queen to stop mate in 1.

Returning to the list of advantages...

The defending side has

1. a King must on a vulnerable square

2. either all of his King's critical flight squares eliminated by his own pieces, the edge of the board, or being controlled by a mating side piece or is about to have them completely removed as a result of the upcoming mating move

3. no effective attack on the mating square

4. no available piece that can interpose between the mating square and the King in long-range checkmates

Tactics

In closing, here is a rough mapping of where common tactics fit on the grid:

| Move | ... away from a square | ... onto a square |

| my piece |

|

|

| his piece |

|

|

Sources:

- Tasc Chess Tutor version 2.01,Tasc B. V. Holland 1995-1999

- The Mammoth Book of Chess by Graham Burgess, Carroll And Graf 1997, 2000

-=-=-=-=-

please leave a comment.

CD - I agree - it boils down to looking hard for the tactic if it is there. Part of the reason I was bent on doing this was to shift into systematic "advantage" thinking so I (or anybody) really can nail down what's going on, thus avoiding ambiguous naming conventions.

I think there might be a better, simpler way to do what I was aiming for, but it's a start.

Tempo, I look forward to seeing your upcoming post.

BD and GK - I had not thought of doing a document, as this Blog makes it available to everyone regardless of platform. I can probably whip one up and email it to whoever once it, but it might not look pretty (right away at least).

A removal of the guard sacrifice check which forces the King X bishop capture allowing the queen to be freely captured.

Your second example, I agree is as an example of overpowering to control the mating square. A forcing sequence to control the mating square. In a way it is also a removal of the guard since it forces the removal of the guarding pawn ,the only guard against mate. I am also trying to remember the names of classic mating paterns this one is an Anastasia Mate.

Tak, glad you like the post, and I never heard of Double Grimshaw before. It's interesting that you brought up one of those naming ambiguities: - "Removal of the Guard" v. "Threatening (or attacking, harassing, etc.) the Guard". I see the Bishop xf7 as threatening a Guard (forgetting for a moment that the Guard is a King). These are sometimes lumped together. They seem very different to me, as one starts with a capture to hang or weaken a piece, while the other doesn't necessarily start with a capture and threatens a defender.

Here I go again, yak yak yak. Those names have been helpful for me as well, though they leave a wee bit to be desired :-).

A pawn push could yield advantages for both sides, depending on the position. Having new lines open and other lines closed could be very double-edged, too.

Still, it boils down weighing advantages for both sides, and I don't see why the list advantages for wouldn't be finite (though large!).

If you know alot about handling pawns, you probably could meld that into an advantage grid with other factors pretty easily.

Then a simple combination is something you can do with two pieces- like a discovered attack or a deflection.

Then a complex combination is something you build out of the above two.

Excellent work!

It shows that you have really been putting a lot of thought into your approach.

I usually find that I work best using a similar approach. If I can break something down into it's most basic elements it is so much easier for me to reassemble it into a format/language that I can easily identify. Using mating patterns is a good idea because those moves are forced. A check has to be answered and takes priority over all of the chess rules excluding the basics of board setup and piece movement.

I like the new colors. :)

http://goldgame.org/

http://goldonsale.net/

http://lifehealth-club.com/

http://www.4rsgold.com/christmas/active.html

http://www.fzf.com/christmas/christmas.html

Link: https://www.poecurrency.com/

<< Home